our neighborhood

welcome to the far west village

The Far West Village, our neighborhood, is the area located along the Hudson River waterfront between Horatio and Barrow Streets, where Greenwich Village began. Its long history as a maritime-industrial and residential neighborhood has left us with a treasure trove of historic buildings spanning about a hundred years and a broad range of styles and building types. Architecturally, there are more than twenty early 19th century and more than thirty-five late 19th century buildings, with the remaining predominantly comprised of early 20th century structures.

Many of the Far West Village’s quiet, narrow streets - virtually unchanged since the early 1800's - have a refreshing smallness of scale. Federal, Greek Revival and Anglo-Italianate town houses share the blocks of the Far West Village with a smattering of architectural eccentricities, late 19th- and early 20th-century apartment buildings and some more recent arrivals.

The streets themselves are a crazy quilt of diagonals and curves that mostly predate the rigid grid pattern to the north. Restaurants and nightclubs crowd onto the streets. Today, the area is still less commercial than mainstream Greenwich Village further east and offers a lively mix of dive bars and upscale restaurants. In all, there are about 250 restaurants in the neighborhood with outdoor dining. Fashionable shops along Bleecker contrast with the funkier shopping and dining promenade of Hudson Street.

And then there's the Wild West, the land of looming, boxlike warehouses west of Hudson up to the river. This is our neighborhood; decaying piers, rusting railroad trestles and the vague smell of beef wafting from the buildings of the old Gansevoort meat market.

Today, the waterfront is transformed and the Hudson River Park, with its shaded lawns, refurbished piers and busy bike path, is a focal point for life on the far west side, and the Meatpacking District to our north is a trendy neighbor which shares a history of transformation.

(Adapted from a NYT article by Andrew L. Yarrow, April 18, 1986)

the far west village, a transformation in our lifetime

the far west village in the 18th and 19th centuries

Long before it was home to early European settlements, the present-day West Village was inhabited by the Lenape people and called ''Sapokanickan'' (or ''wet fields'' or "Tobacco Fields". At that time, it was a place of trading and canoe landing.

In the 18th century, much of the present-day Far West Village’s land was created from landfill. The area was transformed into a tobacco plantation by the Dutch, who called it ''Bossen Bouwerie'' (or ''farm in the woods''). Under the English around 1800, this isolated outpost was renamed Grinwich and it became a country village that lasted right into the early 19th century, before a series of smallpox and yellow-fever epidemics in lower Manhattan sent New Yorkers scurrying northward.

''In the 1810's and 20's, Greenwich was a charming English settlement. The city grew in the 1850's and 60's, but the Village was always a place out of time. Town houses were built, followed by larger apartment houses for the immigrants who arrived later in the century. Industry was huddled to the west, on landfill near the river.

The beginnings of what would become a huge wave of Irish immigration to New York City began in the early 19th century. Many of the first immigrants ended up in the growing Irish neighborhoods of Lower Manhattan where New York, with 771 miles of wharfage, was becoming a center of global commerce. Many Irish came to work as domestic servants, construction workers, and longshoremen, helping to construct New York’s port.

Middle-class Irish saloons filled out the growing neighborhood. Saloons and bars were particularly important fixtures during this period. Many were opened by the older generation of Irish immigrants who had accrued some wealth and often were also leaders of the community. For instance, in the mid-20th century, Whitey Munson, the grandfather of the longtime owner of the White Horse Tavern, James Munson, was a boss at the docks, and a dominant figure in the longshoremen community and the Irish community at large. Of course, the White Horse Tavern is famed as where Dylan Thomas partook of many a drink.

(thanks to www.villagepreservation.org)

Two significant waves of Irish immigration followed: one during the famine years of 1845 through the 1850s, and another after the American Civil War. By the end of the 19th century, the edge of the West Village was dominated by the Irish. Along St. Luke’s Place could be found a row of houses inhabited by the Irish middle-class, descendants of earlier immigrants.

To the west of this prosperous enclave, further west in the Village, dozens of tenements had emerged, housing working-class Irish immigrants, who worked in unskilled and semi-skilled positions. Many were longshoremen who worked on the busy docks.

Tenth and Eleventh Avenues that extended throughout the West Village were known as Death Avenue in the 19th century and for good reason. By mid-century, the Hudson River Rail Road constructed freight train tracks up 10th Avenue at street level with no barriers to protect pedestrians and cars from the trains. It was estimated well over 500 people died and nearly 1,600 were injured on Death Avenue from around 1850 to 1910.

In an attempt to solve this growing problem, a city ordinance created the West Side Cowboys who rode alongside the train tracks waving a red flag or red lantern to warn drivers and pedestrians of oncoming trains. Until 1941, these cowboys would ride down 10th Avenue escorting freight cars. Even though the trains often were as slow as six miles per hour, injuries still continued, making it necessary for the cowboys to continue working to save pedestrians. The last stretch of tracks was removed in 1941 after about a decade of removal efforts.

the far west village in the 20th century

The West Village was historically known as an important landmark on the map of American bohemian culture in the early to mid-20th century. The district was known for its colorful, artistic inhabitants and the alternative culture they popularized. Thanks to the progressive attitudes of many of its residents, the village has become a center of new movements and ideas, whether political, artistic or cultural.

This tradition as an avant-garde, alternative cultural enclave was established in the 19th and 20th centuries when small printing houses, art galleries and experimental theater flourished. Known as 'Little Bohemia' since 1916, the West Village is in some ways the epicenter of the West Side's bohemian lifestyle, with classical artists' lofts and Julian Schnabel's Palazzo Chupi, and the Westbeth Artists Community.

In 1924, the Cherry Lane Theater was established at 38 Commerce Street. It is the oldest Off-Broadway theater still operating in New York City. A landmark in the Greenwich Village cultural landscape, the building was built as a farm silo in 1817 and served as a tobacco warehouse and It was also used as a box factory. The Cherry Lane Playhouse opened on March 24, 1924 with the play The Man Who Ate the Popomak. Eugene O’Neill, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, and W.H. Auden all had plays produced at the theater in its early years.

In the 1940s, the Living Theater, Absurd Theater and Downtown Theater movements all took root here, building a reputation as a venue for aspiring playwrights and up-and-coming performers to present their work.

When Barney Josephson opened Café Society at 1 Sheridan Square in 1938, the village hosted America's first racially integrated nightclub for both musicians and customers. Café Society showcased African-American talent and was intended to be an American version of the political cabaret Josephson had seen in Europe before World War I. Though it was only open for a decade, Cafe Society played an important role in integrating musicians of all races. The club featured a premiere of Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit.”

He stated, “I wanted a club where Blacks and whites worked together behind the footlights and sat together out front… There wasn’t, so far as I know, a place like it in New York or in the whole country.” He decided to open the club in the West Village, a predominantly white neighborhood, and advertised it as “The Wrong Place for the Right People.” The club treated Black and white customers as equally as possible given the political climate, and it helped launch the careers of Lena Horne and Ruth Brown. The club, as part of efforts to further integrate other music venues, raised money for left-wing causes.

Notable performers included Pearl Bailey, Count Basie, Nat King Cole, John Coltrane and Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald, Coleman Hawkins, Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, Burl Ives, Reed Berry, Anita O'Day, Charlie Parker, Les Paul and Mary Ford, Paul Robson, Kay Starr, Art Tatum, Sarah Vaughan, Dinah Washington, Josh White, Teddy Wilson, Lester Young and The Weavers.

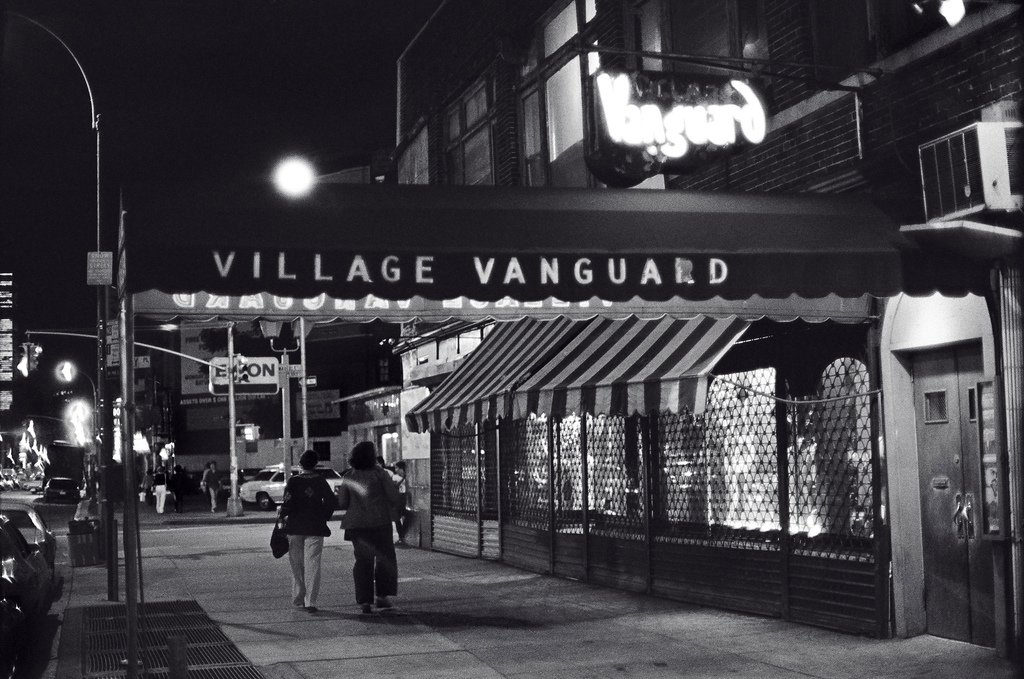

The Village Vanguard is another Village icon, opened on February 22, 1935. Originally, the club presented folk music and beat poetry, but it became primarily a jazz music venue in 1957. It has hosted many highly renowned jazz musicians since then, and today is the oldest operating jazz club in New York City.

The annual Greenwich Village Halloween Parade, started in 1974 by Greenwich Village puppeteer and mask maker Ralph Frey, is the world's largest Halloween parade and the only major nighttime parade in America, attracting 60,000 people. Over 200 costumed participants, 2 million in-person spectators and audiences from all over the world. Over 100 million TV viewers.

(Borrowed from The Academic Accelerator: Academic Accelerator | Accelerate Your Scholarly Research (academic-accelerator.com))

The Westbeth Artists Community is a storied complex providing living and working space for artists, though five decades ago, the building had a very different purpose. The 13-building complex was originally part of the Bell Laboratories Building at 463 West Street and was the site of major scientific breakthroughs from 1898 to 1966. Such innovations include black-and-white and color television, the phonograph record, radar, and vacuum tubes. Additionally, some research for the Manhattan Project was conducted at the site, and the first baseball game was broadcast through Bell.

After Bell Labs moved, the building was converted into the Westbeth Artists Community, creating live-work spaces for 384 artists who met certain income requirements. The building was renovated to include rehearsal studios, commercial spaces, and performance halls. Early artists who resided there included photographer Diane Arbus, artist Hans Haacke, and Vin Diesel. Cultural organizations including The New School for Drama, the Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance, and LAByrinth Theater Company also moved into the space.

The High Line, today one of Manhattan’s most frequented spots, was originally built for trains to travel above ground following multiple deaths along 10th Avenue from locomotive accidents. Trains went back and forth on the over two-mile route, distributing all sorts of goods from refrigerated meats to Oreo cookies along the west side of Manhattan.

However, by the 1950s, the High Line was not as necessary with the rise of container shipping ports along the New Jersey side of the Hudson River, rendering the lower third of the High Line unnecessary. As more buildings were constructed, major sections of the High Line were taken down, including the section that would become the Jacob K. Javits Center. Though most sections were destroyed, two still remain, both of which actually went through buildings: the Westbeth Artists Residence and the West Coast Apartments. Both of these sites show some semblance of what was formerly the route.

In 1980, the railway’s final train made its way up the West Side, ending the more-than-century-long use of trains as a primary transport to and from the factories and warehouses of the Meatpacking District.

the far west village in the new millennium

In more recent years, there have been some controversial buildings erected in our neighborhood.

Right across the road from our building, at 360 West 11th Street there is a residential building that was constructed in the style of a Venetian palazzo. Called Palazzo Chupi, the building was designed by artist and filmmaker Julian Schnabel and constructed atop a former horse stable that was converted into apartments. The name comes from a Spanish lollipop brand called Chupa Chups, and the palazzo was painted a bright pink. The original building dates back to around 1915 and also served as a perfume studio.

The building stands at 12 stories, and construction was very fast to beat potential height limitations. The building includes a large terrace with Italian-inspired arches, and parts of the building resemble Padua’s Scrovegni Chapel. Madonna, Johnny Depp, and Richard Gere all lived in the building, the first four floors of which are Schnabel’s. The palazzo has been met with mixed critical reviews; while some have considered the building an authentic representation of Italian architecture, others including Andrew Berman of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation called it “woefully out of context and a monument to this guy’s ego.” Berman has also described the Palazzo Chupi as "an exploded Malibu Barbie house."

One wry commentator whose views are always a welcome tonic thinks of Chupi as an homage to transsexual prostitutes: said Paul Rudnick, a novelist and playwright who lives across the street: "It's much more in the tradition of the West Village, which is supposed to be outrageous and theatrical, than all those glass towers. When the transsexuals left it seems they were reincarnated as real estate. At least the Palazzo does them proud."

In stark contrast, the Perry Street Towers, designed by Richard Meier in 2003 and located a mere two blocks from our building, are known for their distinctive and original residential architecture, with see-through designs that emphasize views of the Hudson River. Many neighbors in the Village were unhappy about the buildings' juxtaposition of white glass to faded red brick and gray cinder block, but it was the stunning failures in design that caught more media attention. The towers have been criticized for their chic residents being completely exposed in their full-story apartments until they add some curtains and attracted much negative publicity following reports of leaks, construction delays, heating and cooling nightmares, and other problems that inconvenienced rich and famous tenants like Nicole Kidman, Calvin Klein, Hugh Jackman and Martha Stewart.

The Whitney Museum’s new location in the West Village between the Highline and the Hudson RIver is not just a major event in the culture of the city, it brought to the area a unique architectural site. As the New York TImes put it when the museum opened:

“From the West, along the Hudson River, it looks ungainly and a little odd, vaguely nautical, bulging where the shoreline jogs, a ship on blocks perhaps, alluding to one of New York’s bedrock industries from long ago.

The Whitney was founded in 1931 by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, a wealthy and prominent American socialite and art patron. From 1966 to 2014, the Whitney was located on the Upper East Side; it closed in October 2014 to relocate to a new building in the Meatpacking District/West Village, which opened in May 2015, expanding the museum exhibition space to 50,000 square feet. It was designed by Renzo Piano. In 2022, the Whitney was the 67th most-visited art museum in the world and the 10th most-visited art museum in the United States.

The Whitney focuses on collecting and preserving 20th- and 21st-century American art. Its permanent collection, spanning the late-19th century to the present, comprises more than 25,000 paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, photographs, films, videos, and artifacts of new media by more than 3,500 artists. It places particular emphasis on exhibiting the work of living artists.

When it opened, a New York TImes article heralding the new museum went further and commented on the implications for our Far West Village neighborhood:

“It’s a glittery emblem of new urban capital, shipping now having gone the way of so much else in the neighborhood.

From the north, it resembles something else, a factory or maybe a hospital, with a utilitarian wall of windows and a cluster of pipes climbing the pale-blue steel facade toward a rooftop of exposed mechanicals.

And from the east, its bulk suddenly hides behind the High Line, above a light-filled, glass-enclosed ground floor that gives views straight through the building to the water.

By moving downtown from Madison Avenue, the Whitney Museum of American Art does more than drop a cultural anchor at the High Line’s base, in the deracinated meatpacking district.

The move confirms a definitive shift in the city’s social geography, which has been decades coming.

It ratifies Chelsea and the once-funky far West Village as something closer to what the Upper East Side used to be, say, circa 1966, the year Marcel Breuer’s Whitney building opened at 75th Street. Those neighborhoods serve up the same cocktail of money, real estate, fashion and art — except that the financiers, Hollywood stars and other haute bourgeois bohemians stand in for the old Social Register crowd.”

read what the media had to say about our neighborhood in 1982 and 2004

-

The Far West Village

THE FAR WEST VILLAGE

''WAY out west of Hudson Street'' is how Greenwich Villagers, viewing the world from their expensive little Bohemia, used to think of the cheaper dockside quarter to the west. Now that area has emerged as the dramatically expanding residential quarter of the 1980's. Moving beyond Bohemia into $100,000-a-year-and-up chic, it is variously known as the New West Village, the West West Village, the Real West Village or the Far West Village.

With a suitably westward-ho drive and a sort of West Coast innovativeness, it has pushed past its 19th-century red-brick and brownstone houses to adapt unlikely terrain to human habitation. Prospectors for unconventional housing at almost any price find open living spaces and the rakish bulks of reclaimed warehouses and coldstorage plants alongside cobblestoned, Greek Revival quaintness. Traditional apartment houses, none truly high-rise, are outnumbered by sturdy, 100-year-old ''tenements'' refurbished to attract the young and prosperous, even as Irish or Italian oldtimers still lean on pillows to watch the world from upper windows.

''The big push is already on to get high-rises along the river,'' one real estate broker said. The linchpin of the developing community is the imminent $50 million conversion of the 10-story former Federal Archives Building, the area's largest structure and vacant since 1974. The high-ceilinged, block-square Romanesque landmark, bounded by Christopher, Barrow, Washington and Greenwich Streets, will be a 350-apartment cooperative, with retail and community space.

From truck-clotted West Street on the river, the Far West Village runs inland only three crosstown blocks across Washington Street, Greenwich Street and Hudson (the southern extension of Eighth Avenue) - or, in some minds, to Bleecker for one five-block stretch between Christopher and Bank Streets. Southward from its north boundary at West 14th Street, the area extends 15 or 18 blocks - to Morton or West Houston, depending on who is counting.

To stem the decline of jobs, nonresidential zoning has been stiffened in the area's north and south extremities: the Gansevoort wholesale-meat district, just below 14th Street, and the ''graphic arts and trucking district,'' which meanders below Morton Street toward Houston. MANY of the ''private'' houses go back to the 1840s, soon after the a rea was turned from farmland into lots, and the Greenwich Village H istoric District extends westward to the middle of Washington S treet. Nearly all the houses have been divided into apartments ( duplexes, floor-throughs or smaller), generally by owner-occupants, o r are jointly owned.

Two or three decades ago, when many houses had declined into rooming houses but pier operations were already withering, creeping blight seemed to destine the whole area to urban renewal by bulldozer and high-rise development. Activists led by Jane Jacobs, the writer on urban planning, beat back that threat, and community vigilance and economic conditions have since led to a ''renewal'' more in the area's own image. But residents peer into the not-quite-settled question of the Westway, the proposed six-lane highway along the Hudson River from the Battery to 42d Street, as if into a crystal ball, even while disagreeing on what they see.

''You can't talk West Village without talking Westway - the whole future hangs on it,'' says James Shaw, chairman of the West Village Committee. The road would run underground the length of the West Village, with landfill creating new residential and park property in the river. The only ''parks'' now are two play-and-sitting areas at Abingdon Square and two sports courts, far north and far south.

Served remotely or scantily by subway and bus, the Far West Village has remained, except for Christopher Street, a sort of backwater, without Greenwich Village's tour buses, walking tours and weekend hordes. But the Far West cherishes its peculiar surprises: A clapboard cottage moved to its own lawn at Greenwich and Charles Streets, dwarfed by buildings that, at nine or 10 stories, are tall for the area. The Amos Farm, a nursery plot and garden store on Hudson at 10th Street that still carries the name of an original farm in the area. A sunbathing pier at the foot of Morton Street that is moorage for ''the Greenwich Village Navy'' - two Board of Education training ships. A defunct elevated railroad spur that appears to run right through three of the newest conversions on West Street.

In 1970, 6,400 people lived in the entire area west of Hudson. The 1980 census counted just under 8,000, by now a thoroughly out-of-date total. Sixteen percent were from black, Hispanic or other minorities.

Although the area has a large homosexual population, it also attracts young, two-paycheck heterosexual couples. Less than onefourth of the 1980 households were ''families'' (married couples with or without children and single parents with children). The entire child population was 635 and 2,700 adults lived alone.

The median age for the whole area was 33, but 668 persons were over 65, with 400 of them living north of Bank Street and many still protected by rent control.

Public schools are nearby P.S. 3 on Hudson Street, which offers an arts-centered ''alternative'' curriculum, and P.S. 41, the main Greenwich Village school on West 11th and Avenue of the Americas. With 800 pupils, P.S. 41 has 74 percent reading at or above grade level, 112th among the city's 627 elementary schools. P.S. 3, with 325 pupils, ranks 147th with a 70 percent score. Private schools include the Village Community School, St. Luke's and the West Village Nursery School.

Thus far, retail business has not increased in proportion to the new population, and it is still a fair sprint to Bleecker Street's gourmet and ethnic food shops, boutiques, hardware stores, decorators and antique shops. Movies are also a long trek away, but the lively theater west of Seventh Avenue includes the Lucille Lortel (formerly Theater de Lys), Cherry Lane, Actors Playhouse, Circle Repertory, Perry Street and others (including the Herbert Berghof Studio).

The West Village plethora of restaurants is edging farther west, with uptowners attracted to perhaps the Village Green, La Ripaille or The Heavenly Host (complete with harpsichord) on Hudson, Hornblower's on Horatio, K.O.'s or Trattoria da Alfredo on Bank. The old working-class bars have been ''discovered,'' in the earlier tradition of the White Horse on Hudson, and even the waterfront dives are getting fancier - and more expensive.

While burglaries in the area have dropped below last year's first three months, robberies are up 70 percent while holding steady in the rest of the Sixth Precinct. Officer Thomas Knobel, noting that ''the population doubles on weekends,'' said most of the trouble was around the homosexual bars and the piers between 11 A.M. and 5 A.M. Urging residents to ''stay off West Street at night,'' he said the precinct was ''trying to clean up'' the conditions there. THE spectacular increase in housing has come mainly through conversion of commercial and manufacturing buildings to living lofts and apartments. Mark Blau, one of the new breed of conversion specialists (he turned a former stable on Horatio Street into a distinctive co-op), puts the number west of Hudson at ''maybe 2,000 completed already with, you could safely say, thousands more in the pipeline.''

The old Federal House of Detention on West Street has become a loft co-op. The former Sixth Precinct stationhouse is an apartment house called Le Gendarme. Printing House Square was a printing company. Recycled warehouses include Shephard House, the Romanesque (rents from $850 for a studio to $2,895 for the penthouse), the Towers and Waywest, where a two-bedroom ground-floor apartment goes for $160,000 with $245 maintenance. Manhattan Refrigerating Company, which served the meat-market district, is now the 300-unit West Coast rental apartments (studios, $900; 1-bedroom, $1,200) - and developers with faith in future zoning relaxation are jockeying for position in the meat district itself.

''To find co-ops here under $100,000 is really tough,'' said David Puchkoff, Waywest's owner. Said Mr. Blau, ''In this area you're talking about $100 per square foot for a basic, open-plan co-op purchase and maybe $150 to $160 per square foot for completely finished, with good kitchens and baths.''

''Townhouse prices here are pretty much holding at $400,000 to $600,000 but few good ones are on the market,'' said Mary Johnson, a real estate broker. ''Interestingly enough,'' said Patricia Mason, another broker, ''none has gone over $1 million yet - but they will.'' Calling $450,000 to $500,000 ''really the starting point for brownstones,'' she said she had ''a tiny little one for $290,000.''

Typical rents for apartments in houses are $600 to $750 for studios, $900 to $1,400 for one-bedrooms and $1,400 to $2,000 for two-bedrooms.

Read it in the NYT archives here

-

Down by the Riverside

On a recent icy morning, a stretch limo glided up Greenwich Street to No. 497, an eleven-story luxury condominium rising behind a dramatically rippled glass exterior—an anomaly among blocks ofsquat warehouses mitigated only by the occasional café and dive bar. Carlo Salvi, an Italian entrepreneur with wild black hair who owns, among other less glamorous and more profitable companies, half of the modeling agency that reps Naomi Campbell, emerged from the car, trailed by a middle-aged assistant. Salvi is thinking about adding another address to his collection of homes—he’s already staked out Miami, Lugano, and London—so he’s checking out the Greenwich Street Project, where Campbell, Jay-Z, and Isabella Rossellini have toured lofts, and artist Richard Tuttle, among more than a dozen others, recently closed a deal. “I am in New York for only two months a year, so I don’t need a terrace,” Salvi says, surveying the massive wraparound glass balconies of the $6.6 million, 3,600-square-foot penthouse duplex that will be delivered raw. He guesses out loud that it would cost him another $1 million before he’d be finished, especially if he plans to take his broker’s advice to build a central glass staircase like the one in Apple’s Soho store. “I don’t need it, but I’ll buy it if I find a good deal.” Through slanted floor-to-ceiling windows, the unobstructed views of the river and the freshly renovated stretch of the $400 million Hudson River Park below are spectacular, even if a winter storm has turned the landscape into an icy tundra.

There’s a real-estate revolution afoot on downtown’s Far West Side, and it’s a revolution from above. Salvi typifies a new breed of buyers being targeted by ambitious developers who are colonizing the Hudson River shoreline from the western edge of Soho north to the Far West Village. Speculators are betting that these high-end homesteaders will shell out millions for eye-catching architecture, picture-postcard sunsets, and such luxury amenities as resistance pools and guest apartments. The ideal buyer is not dissuaded by the fact that it’s all but impossible to hail a cab on these frigid, windy corners, since he’s likely to have a car and driver idling curbside, not to mention another home at the ready in gentler climes. There are no snobby co-op boards to impress. And let’s face it: The private chef may be the only one prowling the forbidding side streets in search of black truffles or aged Gouda.

The Greenwich Street Project, brainchild of British developer Jonathon Carroll and Dutch architect Winka Dubbeldam, is just the first stop on Salvi’s neighborhood tour. On the same block, the fourteen-story 505 Greenwich Street, which opened its sales office in early January, touts a list of 400 prospective buyers waiting to look at apartments. A dozen blocks north, buyers are moving into Richard Meier’s celebrated twin glass towers at 173 and 176 Perry Street, developed by Richard Born, or eagerly awaiting a third, even more luxurious Meier tower going up next door at 165 Charles Street for developers Izak Senbahar and Simon Elias, who are, like the others, asking $1,500 to $2,500 per square foot for their new digs.

A short walk from the Meier matrix is Morton Square, developer Jules Demchick’s sprawling compound of condos, townhouses, and lofts designed by Costas Kondylis, where buyers as disparate as artist Chuck Close and the teen television-and-tabloid stars Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen will be moving in. And the West Village land rush isn’t over, either: On January 15, the Related Companies (which brought us the Time Warner Center on Columbus Circle) signed a deal to develop high-rise condos on the site of the Superior Printing Ink Company, a 33,000-square-foot lot about four blocks north of the Perry Street towers, at Bethune and West 12th Street. “It’s the last and best remaining site,” boasts Related’s 35-year-old golden-boy president, Jeff Blau.

The dream these developers and their world-class designers share is the total transformation of the lower West Side riverfront, an area that extends from 14th Street south to Canal Street and from Hudson Street west to the river. Until recently an industrial wasteland a little too far from the cobblestones and quaint townhouses of the West Village and Soho, the area has quickly become a status sphere replete with Park Avenue amenities—and Park Avenue sticker shock. What distinguishes the new buildings beyond their luxe accoutrements is their bold attack on the skyline, bringing airy, spacious, open residential design more typically associated with California and Europe to the banks of the Hudson.

The new condo coast owes its development in part to the Hudson River Park renaissance—Rollerblading! Trapeze school! Kayaking! Jogging trail! But it’s also a consequence of developers running out of commercial buildings to convert in Tribeca and Soho—and being unable, because of zoning, to go vertical in the meatpacking district. New buildings also lend themselves to high-tech amenities and luxury appointments (pet spa, anyone?). Embellish them with cutting-edge, brand-name architecture, and you’ve got catnip for the city’s restless buyers ever in search of the latest trophy home.

“You’re seeing a lot of your typical Upper East Side buyers moving downtown for something hipper, cooler, with better views and new modern buildings,” Blau says. “The people who are buying in this market are used to having their own drivers.”

And they’re willing to pay for parking garages, proximity to the West Side heliport, gyms with spas, and 24-hour concierges in brand-new buildings, rather than conversions of warehouses and factories like their Tribeca predecessors.

The neighborhoods into which they’re moving range from the yuppie-friendly Far West Village at the north end, adjacent to the quaint cafés and chic boutiques that line the narrow streets of the West Village, to gritty pre-gentrification West Soho at the south end, an area almost completely lacking in amenities.

Not surprisingly, current residents are somewhat ambivalent about the impending glamorization of the last stretch of viable real estate along the West Side Highway. High-rise development is allowable only because it’s outside the historic zone, which prompts West Villagers to worry that it will end up blocking the light and air—not to mention their river views.

“The major concern of locals,” adds Arthur Strickler, district manager of Community Board 2, which oversees the Far West Village, “is we don’t want to have our side of the Hudson River mirror the New Jersey side.”

If you’re looking for the man most responsible for luring the chauffeured set to Manhattan’s newest Gold Coast wannabe, look no further than Richard Meier. His name is the mantra uttered by downtown brokers and developers spinning the rationale for charging Central Park prices for Abingdon Square environs. When Richard Born broke ground three years ago on the matching Meier-designed glass towers at the river end of Perry Street’s windy corridor, Martha Stewart, Nicole Kidman, Calvin Klein, real-estate developer Scott Resnick, and Sun Microsystems co-founder William Joy were among the first to spend about $2,000 a square foot for raw space that included concrete floors, de rigueur wraparound floor-to-ceiling windows, and vertigo-inducing terraces. The only boldface name to have moved in so far is Rita Schrager, the former ballet dancer and ex-wife of hotelier Ian Schrager (though Boy From Oz star Hugh Jackman is renting there). But the condo board has already been elected: Resnick, Joy, Ian Schrager, and president Calvin Klein, who has almost finished his $14 million triplex.

Bordered by West Houston Street to the south, Hudson Street to the east, and West 14th Street to the north, the Far West Village—the northern end of the new Condo Coast—is only a few blocks from the area where Gwyneth Paltrow, Julianne Moore, and Anna Wintour live in nineteenth-century townhouses that have been protected by the Greenwich Village Historic District since 1969. It’s family-friendly, though the riverfront has yet to have a big family presence. Public School 3 and the Greenwich Village Middle School, both on Hudson Street, have some of the city’s highest test scores, and St. Luke’s School is also a desirable private-school option for the deep-pocketed buyer.

Of course, not everyone is convinced that the new development will mesh with the surrounding area. “It’s really a separate neighborhood, it’s so far west,” says hotelier Jeff Klein, who owns a West Village townhouse and midtown’s City Club Hotel. “Two years from now, when Nicole and all of them get out of there, the glamour will be deflated and it’s not going to be as expensive. It’s a very inconvenient area. It’s not a neighborhood, even though two blocks east is great.

“If you look at East End Avenue, that was created as an expensive enclave,” Klein continues, “but the prices per square foot are not as expensive as Fifth Avenue. The more central you are in the city, the better off you are.”

But the riverfront really is pretty central, especially if, like Kidman, you travel by Town Car and helicopter. It may seem like the end of the world—or at least like Jersey City—but there’s actually a dry cleaner and a parking garage on the same block as the Perry Street towers, which are just a few blocks from established shops like Magnolia Bakery, home of the city’s most celebrated cupcake, and around the corner from Wallsé, one of the area’s top-rated restaurants.

“All the old West Village people, like Lou Reed, Julian Schnabel, and Laurie Anderson, come in here, and I hear stories about before that are much different from what I see now,” says Kurt Gutenbrunner, Wallsé’s Austrian chef-owner. “Look at the traffic! When I came here in 2000, I never would have thought Jean-Georges would be down the street, and now he’ll be in the Meier building. I’m not so lonely here anymore.”

Soon he’ll also be joined by the all-star team renovating Le Zoo, at 314 West 11th Street (about three blocks from the Perry Street towers). Mario Batali and Bono are among the backers of the new restaurant, slated to reopen by next spring with chef April Bloomfield, formerly of London’s River Cafe, a posh Italian restaurant.

“You’re seeing a lot of your typical Upper East Side buyers moving downtown for something hipper, cooler, with better views.”

The dearth of shops and services isn’t the neighborhood’s only obstacle. The Perry Street towers do look lonely from the street, as only a handful of buyers have finished the raw apartments they purchased, and just one, on the second floor of the south tower, has installed the white shades on the floor-to-ceiling windows that are the only allowable treatments to provide privacy. The Rear Window effect already has some buyers backing out of the building. “It’s not very private,” complains one uptown socialite whose new husband bought a Meier loft before they were engaged and has since put it on the market for $2.75 million. “It’s gorgeous, but it’s more of a bachelor pad.”

Brokers—at least those who haven’t scored commissions in the towers—claim that selling unfinished apartments is a mistake, and 30 percent of the original buyers are trying to flip the Perry Street lofts, with unforeseen difficulty. Born counters that only 5 of 23 units are being flipped, and he doesn’t regret choosing to sell the spaces raw. “Very high-end users want to create their own environment, and whatever I would give them would probably not be what they want,” he says. Martha Stewart’s $6 million, 3,000-square-foot duplex sat on the market for more than a year before finally selling last week, and actor Vincent Gallo recently spent $1.6 million for a loft that the previous owner bought for $2 million—and just sold it since he doesn’t want to live next to a construction site.

The third Meier-designed tower will be unveiled next spring, complete with a 35-seat screening room, a 50-foot lap pool, and a ground-level art gallery. Unlike the Perry Street buildings, there will be two apartments per floor, rather than one. The new sixteen-story tower will have 31 apartments, priced at about $2,500 per square foot. Meier is designing everything from the shower curtains to the kitchen sink.

Meier and Senbahar agreed on “an evolution from the Perry Street towers,” Senbahar says, and in deciding to let Meier finish the interior space, the developer is betting he’ll be able to charge up to 50 percent more than the Perry Street prices: “I’ve always believed that the finished product in New York City is a better product, because construction is a tough business.” Prices will start at $4 million and cap at $20 million for the 5,000-square-foot penthouse with 24-foot-high ceilings.

Senbahar closely resembles Morton Square’s architect, Costas Kondylis (who has also designed most of Donald Trump’s condo towers), and somehow it’s hardly surprising that they’re close friends who vacationed together over New Year’s in St. Bart’s. Both are born-to-the-manner Eastern Europeans, but while Senbahar is aiming for the high-end buyer, Kondylis and Morton Square’s developer, Jules Demchick of J. D. Carlisle Development Corporation, have created a compound suitable for middle-to-upper-class residents.

Just a few blocks south of the Meier towers, Morton Square stretches from West Street to Washington Street, with rounded corners that evoke an ocean liner nestled next to the venerable townhouses and shops that line Barrow and Hudson streets. It’s also barely a block from the Archive, a redbrick Romanesque Revival building, constructed in the 1890s as a warehouse for federal archives, that was converted about ten years ago into luxury apartments—complete with a DÂ’Agostino supermarket, a Crunch gym, a dry cleaner, and paparazzi-hounded tenants including Monica Lewinsky.

“Ours is a whole city block,” says Kondylis, who also designed 285 Lafayette Street four years ago, then a pioneering building and still home to such original buyers as David Bowie and Iman. “We took an urbanistic approach. What makes great urbanistic designs is to be contextual. We didn’t just want to drop objects on the site like Meier did.” Which is not to say that Kondylis doesn’t admire Meier’s design: “The standard is now set,” he declares. Kondylis used Meier’s aesthetic for inspiration, as well as the rounded corners of Chelsea’s massive Starrett-Lehigh building, home to the Martha Stewart Omnimedia mother ship.

But Kondylis didn’t copy Meier, much to his developer’s relief. The façade is composed of just 65 percent glass, and the apartments are delivered finished. “We learned from Meier’s mistakes,” says Demchick, who sports a gold pinkie ring. “We’re trying to create substance and security. Floor-to-ceiling windows are not a secure feeling.”

Brokers list Naomi Watts, Stanley Tucci, and Ally Sheedy among the celebrities who have toured the property more than once, and say that Sheedy is moving in, joining the Olsen twins, who bought a $3.5 million condo in lieu of shacking up in a Greenwich Village dorm next fall, when they plan to attend NYU.

Built on a former United Parcel Service parking lot, the development near the north end of West Street includes a fourteen-story condo tower and six townhouses with loft apartments. They’re slated to be ready by next fall. Morton Square’s sales office opened last summer, and about 62 percent of the units, ranging in size from 1,160 to 4,000 square feet, are said to have sold for $1.1 million to $4.25 million.

With its bicycle room and 24-hour valet staff, Morton Square feels more Upper West Side than West Village—which is precisely why artist Chuck Close and his wife Leslie decided to move there from Central Park West. They liked the underground parking garage, since he’s confined to a wheelchair and uses a van for transportation. But to draw buyers like Close, the creative-minded people whom the Far West Village developers are targeting, Morton Square’s developers also commissioned a lobby installation from trendy glass sculptor Tom Patti and plan to add jazzy features like handprint-recognition technology instead of keys to gain entry to the garage.

They also built West Village–style townhouses and downtown-type lofts for people wanting a Tribeca feel—which seems to be working. Andrew Marcus, a 34-year-old single chiropractor, recently bought a $1.85 million, two-bedroom condo. The river views were a major selling point, drawing him from an apartment he owns in Murray Hill. “You can’t beat being on the water,” says Marcus. “Morton Square is unobstructed. Every night you see the sunset over Jersey City. And I don’t think there’s any better place to be than the West Village, for the downtown nightlife and restaurants.”

The most isolated part of the Condo Coast is the southern extremity: The Greenwich Street Project and 505 Greenwich—just two blocks east of the West Side Highway and one block from UPS’s not-exactly-eye-candy loading docks and parking lots—are pioneers in a primarily commercial area that optimistic developers and brokers have dubbed West Soho or Hudson Square. Young hipsters pack nightlife mainstays like the Ear Inn, Sway, and Don Hill’s, but there is no bakery, shoe-repair shop, or pharmacy within winter walking distance.

Around the corner from the new towers, the Vendome Group is planning a Philip Johnson–designed tower at 328 Spring Street to replace an earlier proposal that was rejected a few years ago by the Board of Standards and Appeals for being too tall.

The Jack Parker Corporation is also building a rental property on Spring Street. And Peter Moore Associates, an architecture-and-development firm, is working on two eight-story condo towers in West Soho that should break ground next fall on Spring Street and Renwick Street and on Washington Street and Canal. Prices figure to average about $900 per square foot and apartments will feature river views. “I think it’s great that developers recognize that good architecture adds value,” says Moore. “It’s better than all this stuff that looks like Battery Park City. I’m excited about what’s going on down here.”

Across from 505 Greenwich’s elaborate sales office on Spring Street is Giorgione, owned by Giorgio DeLuca (of Dean & Deluca). Sources say neighborhood resident DeLuca is now negotiating to take over the restaurant down the block, formerly known as Spring Street (and before that, Theo), between Greenwich and Washington streets—and to transform it into a restaurant and maybe a gourmet market for all the new high-end residents.

Deluca’s timing may prove better than that of his predecessor Jonathan Morr. The BondSt restaurateur had shown the foresight to shoot for three stars in West Soho with Theo—a well-received restaurant that nonetheless failed—but it turned out to be three years too early, even after its reincarnation as the truffle-heavy 325 Spring Street. “It was meant to be an up-and-coming neighborhood, but it was very, very difficult to get people down there,” says Morr. “It was like going to a different state. But the neighborhood is going to boom because of all these new buildings.”

Jane Gladstein of Metropolitan Housing Partners (Soho 25, the Sycamore), which is developing 505 Greenwich Street with financing from Apollo Real Estate, makes the lobby and courtyard planned for 505 Greenwich sound more like a New Age spa than a condo tower: Architect Gary Handel & Associates’ design features river rock, black bamboo, burnished copper, and Jerusalem limestone. The apartments will be delivered finished, with the obligatory Sub-Zero and Viking appliances, a wine cooler, ten-foot-high ceilings, and a flat-screen color-monitor security system. Prices will range from $770,000 for a 725-square-foot one-bedroom apartment to $3.5 million for a 2,500-square-foot three-bedroom penthouse.

Denise Levine, 48, and her 51-year-old husband, Jay, who both work for Con Edison, recently bought a 1,000-square-foot apartment after renting for four years in Battery Park City, where they liked living by the Hudson River.

“We love lower Manhattan, and here is a building that’s really in the middle of everything,” Denise says. “And I like the idea of a relatively youthful neighborhood. There are also nice restaurants in the area and convenient transportation. I wouldn’t say great, but convenient transportation.” The Levines even like the idea that another building is going up next door and that other condo towers are being built nearby, on the waterfront. “I think there will be more services soon in the neighborhood, more restaurants and delis. And everyone has FreshDirect now, so there’s no need for a supermarket.”

Meanwhile, 37-year-old Jonathon Carroll chose not to have a sales office at all for his Greenwich Street Project. The hip Brit, who made a pile of cash as an investment banker in London, wants to spend his money creating something artistic. With a slight resemblance to actor Paul Rudd, he looks the part of the artsy kid in the pack of silver-haired suits. This is his first development project since hiring Winka Dubbeldam in ’97 to design his massive three-bedroom loft at 50 Wooster Street (also home to Claire Danes and Donna Karan). The loft—which has been featured in photo shoots with Lauren Bush for Town & Country, a Law & Order episode, and a Lenny Kravitz album cover—doubles as his office and features a model of the new building and a sample window in the middle of his living room.

But Carroll’s probably going to sell it and move into the Greenwich Street Project’s penthouse—now that Salvi and Jay-Z have passed.

The building’s 23 units range in price from $2 million for a 2,800-square-foot loft to $6.6 million for the 3,600-square-foot penthouse with its 1,700 square feet of outdoor space. There are two elevators, a gym with a sauna and infinity pool, and a shared courtyard. Though three young families have bought lofts, most buyers, says Carroll, either have grown children or none, like Tom Schaller, a 52-year-old architect who recently bought a 2,800-square-foot loft he hopes to move into this summer, after he’s fitted it out with a massive bedroom and a guest room–art studio. He’s a fan of Dubbeldam’s and wanted to live in a building with what he deemed “real architecture.”

Schaller doesn’t expect any inconveniences or lack of amenities. “It’s not as if I’m moving to Nepal,” he says. “There are a lot of things around. But if I had kids, I might worry about it.”

Carroll says he’s sold about 70 percent of the lofts and doesn’t regret delivering them raw, even though other developers and brokers claim it’s made for slow sales.

“It’s always surprised me that New York is the most heterogeneous city there is, but in terms of where people live, it’s the opposite,” says Carroll, who likes to wear his olive-green raver sunglasses inside the apartment and says he only ventures above 14th Street to shop. “I didn’t want to make decisions on interiors for other people.” Call him earnest or disingenuous, but he also insists that money doesn’t matter. “The apartments are selling,” he says.

“We will be sold out in the next two months.” And he believes luxury buyers want to design their own homes: “People buying more than $3 million apartments want to do it their own way.”

When Carroll first bought the former food-storage lot that would become the Greenwich Street project in 2000, 505 Greenwich had not yet been planned and he hadn’t heard anything about the Meier towers. “People thought I was insane,” he says. “There was nothing there.” Frankly, he wouldn’t have minded if it had stayed that way, especially when the simultaneous construction of the adjacent buildings led to some inevitable complications—broken glass, ensuing catfights—that no one wants to talk about, at least on the record. “I would prefer if 505 weren’t there,” he admits on a recent afternoon, wearing designer army pants from Bergdorf’s. “But I knew something would go up there.”

Although Dubbeldam, who moved to New York in 1990 from the Netherlands to attend Columbia’s architecture school, has designed commercial spaces (notably the now-defunct Gear magazine’s fabulous offices), this is her first residential apartment building. The wavy-glass-curtain wall was a choice that reflects an obsession with both form and function: “I wanted the façade to have more interface with the city,” she says. (The other reason was that, at the time Carroll and Dubbeldam applied for the permits, the city’s building code mandated that a new tower had to have an incline after 85 feet in height. But the code changed between the two buildings’ ground-breakings, so 505 Greenwich is taller and straight. “It’s not fair, is it?” Dubbeldam carps.)

Dubbeldam is also moving from a Soho rental into the building this spring, and three buyers have asked her to design their raw lofts. “I love the new neighborhood,” says Dubbeldam, who found the spot for Carroll after they had unsuccessfully scoured Williamsburg, Dumbo, and the Lower East Side.

“It’s on the edge of everything, but it’s not a hot spot yet. It’s a nice, calm environment, and I can go running on the river.”

While some established area residents may resist having the Marc Jacobs set move in, the high-end developments are indisputably good news for area’s struggling small-business owners. To Javier Ortega, chef-owner of Pintxos, a tiny Basque restaurant right across the street from the two new buildings on Greenwich, the future tenants may as well be free gold. Five years ago, he came from Guatemala and opened the restaurant—but while the place fills up on weekends, he has yet to pack a crowd for a $35 dinner, including wine. Next door is Pao!, a popular Portuguese restaurant that was nevertheless almost empty at lunchtime one recent afternoon.

“Now people are coming in, filling three or four tables and looking across the street and saying, ‘Maybe I’ll become a regular customer,’ ” says Ortega. “This is very good for people like me.”

Can the new upscale owners blend into the neighborhood and, ultimately, bring growth to such an out-of-the-way area? “When I came here nine years ago, people said, ‘You’re going to die.’ Now there are five or six restaurants on the block,” says Don Hill’s eponymous owner, whose popular nightclub is adjacent to 505 Greenwich Street. “But I still don’t think families are going to move into the neighborhood. Whether the edgy artists are going to be able to come out of here, where the rent’s going to be so high, is another story. Rock artists are going to be trust-fund babies.”

Strickler also doubts the waterfront-construction boom will abate anytime soon. “It’s the wave of the future,” he notes. “Ninety percent of the warehouses are all converted already. The only thing left is the empty lots.”

What developers can do is make sure the buildings add stature to the skyline. “For the first time in New York, we finally have a real chance to show off some world-class architecture on our riverfront,” adds Related’s Blau. “It’s up to the developers to keep the bar raised high.”

preservation of the west village

Historically, local residents and conservation groups have been concerned about the development of the village and have fought to preserve the neighborhood's architectural and historic integrity.

Believe it or not, in the 1960s, Robert Moses declared the West Village west of Hudson Street blighted and planned to tear it all down in the name of urban renewal. Of course, this was a very different West Village than today, and indeed the deactivated High Line, the crumbling West Side piers, the looming West Side Highway, and the somewhat decrepit waterfront warehouses, factories, and sailors’ hotels did not have quite the polish of today’s West Village. Nevertheless, this was Jane Jacobs’ turf, and where Moses saw blight, she saw diversity and potential.

Fortunately, Jane Jacobs led a successful effort to defeat Moses’ urban renewal plan and preserve this charming and modest section of the West Village close to the waterfront. Not long after, half of the area was landmarked in 1969 as part of the Greenwich Village Historic District. However, the Landmarks authority (LPC) left out the entire Greenwich Village waterfront and almost all of the Far West Village, not to mention the Meatpacking District, the South Village, and most of the 14th Street, Broadway, and University Place corridors. In some instances, these oversights have since been partially corrected, and in other cases is still working to correct.

In May of 2006, landmark protections were finally secured for at least part of the Far West Village and Greenwich Village waterfront, after a multi-year campaign led by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation (GVSHP), a non-profit organization dedicated to the neighborhood's architectural and cultural features and heritage.

The Gansevoort Market Historic District was the first new historic district in Greenwich Village in 34 years. With 112 buildings spread across 11 blocks, it protects the city's distinctive meat processing district of cobbled streets, warehouses and tenements. About 70 percent of the area proposed by the GVSHP in 2000 was designated a Historic District by the LPC in 2003, and the entire area was listed on the State and National Register of Historic Places in 2007. Designated in 2006, the Weehawken Street Historic District is a 3-block, 14-building neighborhood centered on small Weehawken Street near the Hudson River. This Greenwich Village Historic District Extension 1 introduced 46 more buildings in three blocks into the district, preserving warehouses, a former public school, a police station, the old Keller Hotel on Barrow and West St, the former Bell Telephone Laboratory Complex (1861-1963), now containing the Westbeth Artist Community, the home at 159 Charles Street, and an early 19th-century tenement at 354 West 11th Street, which is the building directly across the street from ours. Our building was part of the application for landmarking but did not achieve designation.

Additionally, to limit the size and height of new developments permitted in the neighborhood and to encourage the preservation of existing buildings, Greenwich Village has enacted several situational zoning plans in recent years. The Far West Village rezoning, approved in 2005, was Manhattan's first rezoning in recent years, with new height restrictions and a halt to construction of waterfront high-rise towers in much of the Village. and promoted the reuse of existing buildings. The Washington Street and Greenwich Street rezoning, approved in 2010, was passed in near record time to protect six blocks from oversized hotel development and preserve the low-rise character.

charles lane: a nearby ‘before and after’

The image from 2021 shown here from Google Street View shows West Street between Charles and Perry Streets, where, in 2002 and 2004, veteran architect Richard Meier constructed these glassy residential towers. There’s a Belgian blocked lane in between them; this is Charles Lane, which long ago marked the northern footprint of Newgate Prison, whose image can be found on mosaic plaques of the Christopher Street IRT station. Robert Bracklow’s image of the same spot, #410 through #413 West Street, circa 1900. Charles Lane can be seen in the center, with a slant-roofed machine shop and blacksmith to its left and an iron works and boiler maker on the right. Some kids with a cart pulled by ole Dobbin can be seen on Charles Lane.

Residential property sales prices in the West Village are among the most expensive in the United States, typically exceeding US$2,320 per square foot ($25,000/sqm) in October 2023. The median home sale price in West Village was up 75.1% year-over-year.

learn more about our neighborhood

Discover the history of the nearby Hudson River’s piers and the park they’ve become today

Police, fire stations, schools, public transportation, post offices, libraries